What is Permaculture?

Permaculture has many different definitions, but the best known comes from the late Bill Mollison, one of the key founders of the permaculture movement in the 1970s. In his landmark 1988 book, Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual, he gives the following definition:

Permaculture is the conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystems which have the diversity, stability and resilience of natural ecosystems. It is the harmonious integration of landscape and people providing their food, energy, shelter and other material and non-material needs in a sustainable way.

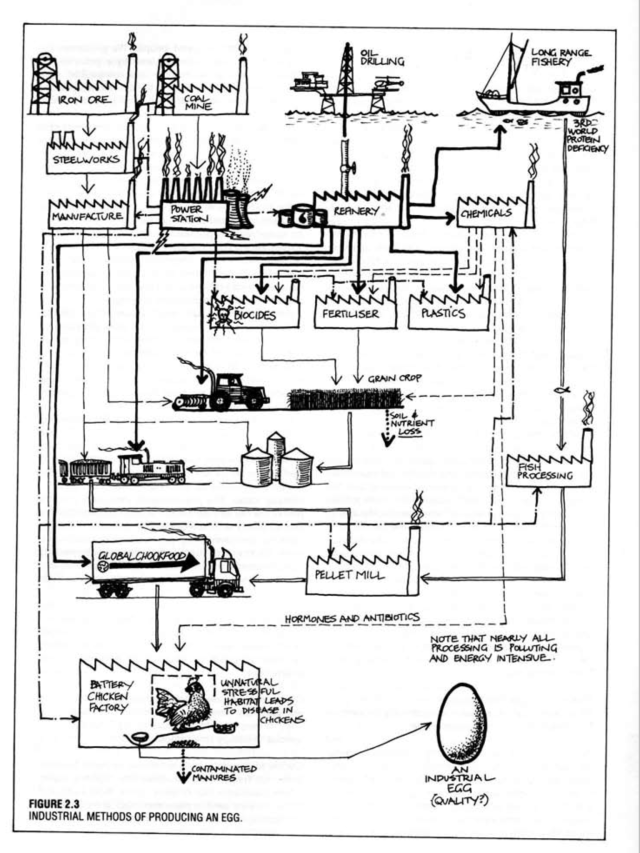

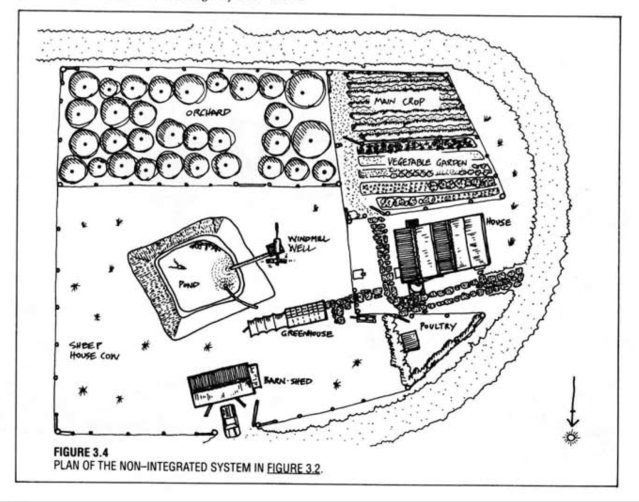

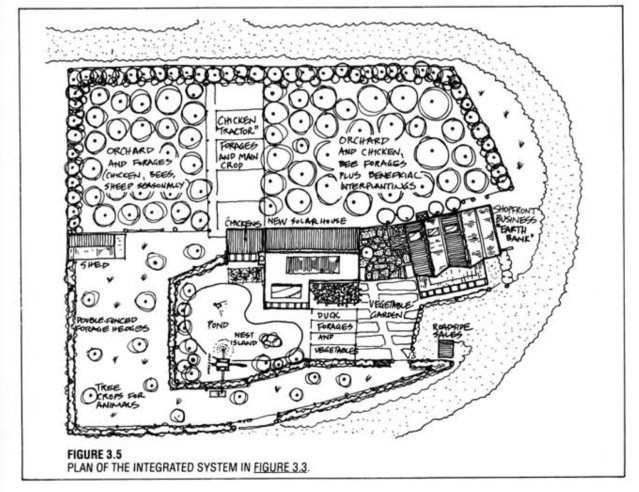

Permaculture is distinct from mainstream or conventional agriculture in that it places a much stronger emphasis on the interconnectedness of living things and natural processes. At the same time, permaculture prefers biological tools over industrial machinery, using animals as an integral part of the farming system. Permaculture is less concerned with increasing and maximizing yields, than it is with keeping the soil and water healthy and self-sustaining over time.

In this sense of being durable and sustainable, permaculture is also known as permanent agriculture. From the perspective of influencing broader social and economic patterns, permaculture is also understood as permanent culture. So permaculture is much bigger and more inclusive than gardening. People who practice permaculture are called permaculturists.

Since completing our Permaculture Design Courses in India, Julia and I are more convinced than ever that permaculture can provide alternatives to our ecological and social problems. Permaculture won’t save the planet, but we can’t save the planet without permaculture. It’s definitely part of truly sustainable and socially just communities.

Now, obviously we’re not experts on permaculture, so this post is simply an attempt to distill what we learned. If you’d like to go deeper into the nuts-and-bolts methods and techniques, there are hundreds of resources and a global permaculture community out there. The best places to start are here, here, here, and here.

In the meantime, if you’re interested in how permaculture can help us reconnect to nature, and how we can apply its principles to make society more fair and sustainable, read on.

Theory of Permaculture

Circles are a central concept in permaculture, symbolizing the circle of life and the interconnection of all living things. Natural processes form repeating cycles of birth, growth, death, decay, and rebirth. Resources in an effective system are therefore used and reused in a fair, sustainable way. Through these cyclic patterns, different elements come together in a mutually supportive way, as in the classic planting technique of the banana circle.

Permaculture goes well beyond gardening, horticulture, and mainstream agriculture because its design and practice requires ethical commitments. The act of planting trees in itself isn’t permaculture. Permaculture means planting trees in a way that their relationship to the soil, to other plants, to the water, to animals, and other elements yield food in a harmonious and sustainable way. To be properly considered as permaculture, any design or technique must meet the following ethical standards:

Earth Care – We must ensure a healthy balance for all life systems to continue and multiply.

People Care – We must provide for people to access all necessary resources.

Fair Share – We must return the surplus and provide for the first two principles to continue the cycle.

Unlike permaculture, the highest priority for conventional and industrial agriculture is to maximize profits. Making money is the most important thing, and this is why mainstream agriculture is obsessed with the extensive use of pesticides, fertilizers, and other tools to generate “bigger and better” yields. And this is why our natural systems are so screwed.

For example, in India alone, farmers are at risk of hunger because land is being converted from diverse food crops that feed their families to monoculture cash crops for market sale. When weather wreaks havoc and consumer tastes change (as they inevitably do), prices collapse, leaving farmers in mountains of debt and driving the most desperate to suicide. This is happening in Australia and the Philippines too.

Permaculture stands in firm opposition to this, by putting the highest premium not on profits, but on the welfare of people and integrity of natural processes. Bill drives home the point further:

The philosophy behind Permaculture is one of working with, rather than against, nature; of protracted and thoughtful observation rather than protracted and thoughtless action; of looking at systems in all their functions, rather than asking only one yield of them; and of allowing systems to demonstrate their own evolution.

Origins of Permaculture

If permaculture sounds very traditional, that’s because it is. It goes right back to our roots. The origins and inspiration lie in the ecological wisdom of ancient and traditional agriculture.

Our permaculture teacher, Narsanna Koppula, always makes the connection to the farming knowledge and practices of rural India before the advent of industrialization. Similarly, strong parallels can be found between the traditional methods of Indian and Filipino farmers, who deeply value soil and water health. In Australia, recent research sheds light on the sophisticated crop cultivation techniques of Aboriginal people, shattering the myth that they were only hunter-gatherers.

Indigenous communities around the world have immense and untapped knowledge about the most effective ways to plant crops, harvest water, nourish the soil, reduce erosion, heal illnesses naturally, and conserve animal populations. While modern society terms them “primitive people”, they in fact possess tremendous wisdom and deep understanding of how our planet works.

In the course of design, permaculturists are guided by permaculture ethics and principles. The ethics essentially stay the same, but permaculturists have adapted and created different principles to suit their diverse styles of practice and their environments. Narsanna’s key design principles are:

- Everything is connected to everything else on this planet.

- Each element should serve multiple functions.

- Each function should be performed by multiple elements.

- Conserve resources and capture energy.

- Waste nothing – turn residue into resources.

- Use appropriate scale – be realistic.

- Diversity is powerful.

- Return the surplus – share with others.

One of the amazing and unconventional ideas of permaculture is its approach to pest control. Permaculturists practice it as effective pest management. Our relationship with insects/animals should be mutually supportive, even if it means less yield and less profit for us. Instead of expecting 110% of the yield, we should be content with at most 80-90% because the creatures also need to eat.

In permaculture you accept that 10-20% of your crop will go to the animal kingdom – and you prepare for that. It makes no sense to give nothing back to a system that consistently gives to you.

Permaculture in ActionPermaculture is a practical design system intended for practical results.

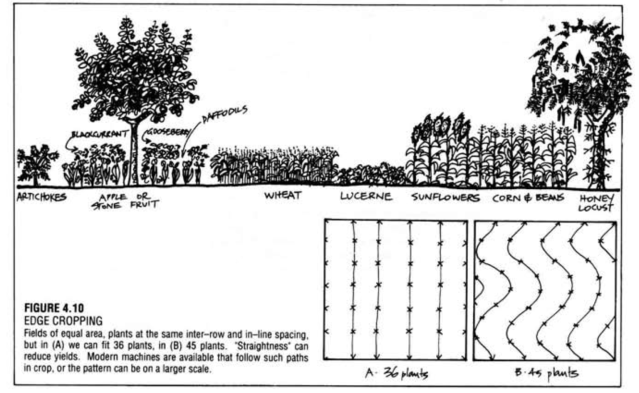

There’s no substitute for being at a farm to see permaculture in action, but here are some notes from Bill’s Design Manual to give you a glimpse of how it works. To the untrained eye, a permaculture farm can look messy. But this is only because we’ve been socially conditioned to think everything has to fit in neat boxes and form straight lines, which nature simply doesn’t do.

We had the opportunity to see permaculture in action at Aranya Farm, and also got to do get our hands dirty (“clean” according to Narsanna) and directly participate. Freshly picked lemongrass and clitoria ternatea were brewed into delicious tea, while soapberries were made into handsoap and body wash.

We explored methods of clay pot irrigation and seed saving. Created our own compost and used ash and natural loofah to wash our dishes.

We also had a go at threshing mung beans – which is seriously hard work! Of course the local women were much better at it.

Why Permaculture?

Permaculture challenges us to rethink not only how we grow and consume our food, but also how we organize our societies – whether they meet human need or simply satisfy corporate greed.

In terms of food consumption, it’s very clear that we’ve become so disconnected from our food, especially those of us who live in wealthy capitalist countries. So disconnected that 20% of Australian children in a recent survey don’t know where their food comes from.

Whether the country we live in is rich or poor, we’re tightly enclosed in a throwaway consumerist culture. Governments and businesses everywhere worship continuous economic growth at the expense of our natural environment. We’re disconnected from nature, period. It’s not a living, breathing entity to us, just another thing to consume.

We’re literally eating our planet.

Even as we consume in staggering amounts, we’re also generating waste at incredible levels. While people in extreme poverty struggle to survive, half of fruit and vegetables grown in the US are thrown away because they don’t look perfect enough for the supermarket shelves.

The toxic consumerist attitude – our mentality, how we eat, how we produce things, what we buy and how often – is probably one of the reasons we’re becoming so unhealthy as individuals and as a planetary community.

There’s got to be a better way.

Permaculture and Social Work

To begin with, we agree it’s important to think and work ethically, which permaculture makes explicit from the get-go. Earth Care? Of course – look after the Earth because we literally can’t live without it. People Care? Definitely – look after each other and make sure everyone’s treated with dignity and respect. Fair Share? Absolutely – there’s no point in obsessively accumulating wealth at the expense of the planet and people.

When permaculture teachers speak about being flexible and adaptable, building on strengths, supporting resilience, encouraging diversity, working with natural processes, and designing effective systems, it feels as though we’re reading from social work texts. In our group meetings, we talked about community participation and gender equality as much as we discussed water harvesting and cropping patterns. It may not be technically correct to say it, but it seems as though social work is permaculture with people, and permaculture is social work with plants.

We’re definitely in our tribe now!

Towards the end of the training, our group feels fired up and ready to take on the world. The enthusiasm is contagious, especially when Narsanna gives us encouraging feedback about out simulated farm designs.

I came across this model from Bill’s co-creator, David Holmgren, which summarizes how the ethics and principles of permaculture come together. David’s ‘Permaculture Flower’ points to how permaculture can inspire us to rethink the way our communities and economies work. This flower reminds me of the ecological perspective of social work.

The possibilities for collaboration with others are exciting.

Permaculture Successes and Limitations

There are so many examples of permaculture successes. One of the most famous is Geoff Lawton’s project in Jordan, where he turned desert into an organic farm and garden in four years. Permaculture projects are viable for meeting food needs of entire communities, including all their working animals. Permaculture techniques are widely recognized for healing the soil, recharging the groundwater, and even bringing barren pastures to life. Permaculture farms run by communities and cooperatives help restore and strengthen community bonds, and assist families and children to eat healthier.

Like social work, permaculture needs to be firmly rooted in reality, so Narsanna is mindful to clarify its limitations. Almost all permaculture projects, including those that achieve a degree of self-reliance, are limited in scale and peak at the village level. Any larger than this, and the machinery and processes of conventional farming have to enter the picture. Modern consumption patterns simply don’t fit the yields of natural food forests and permaculture designs. Until we all learn, for instance, to eat seasonally again, our food habits can’t become fully sustainable.

Permaculture, in today’s world, remains a middle-class phenomenon. Most of us can’t even afford to buy our own homes, let alone establish sustainable permaculture farms. Those who farm on their own land usually depend on income from commercial crops. Even if they want to, it’s usually difficult for conventional farmers to transition to permaculture because the loss of earnings is too great a barrier. Most people who go into permaculture soon after they learn about it already own land and have easier access to credit. They have stable external income, so they don’t need to rely solely on their farms for food and other needs.

Since becoming an organized movement in the late 1970s, permaculture has gained both followers and skeptics, admirers and critics. All things considered, permaculture is a force for good in the world. It has raised global awareness about environmental conservation, exposed the grim realities of corporate agriculture, and driven people to think about better alternatives.

While permaculture evokes an idealistic, even romantic, image of going back to nature and being one with nature, the reality is much more complicated.

Getting started takes a lot of hard work and resources. And it takes time – not just months, but years – to establish even a basic system. With family responsibilities, jobs, mortgages, and other commitment, most people already have enough on their plate and simply can’t devote the attention, effort, and sacrifice required to go full-time.

Ever the realist, Narsanna strongly advises against leaving behind everything to do permaculture. It’s far better to integrate permaculture activities and projects into your daily life, than to make your entire life revolve around permaculture.

Permaculture is inclusive, but it’s not for everyone. Not yet.

Perhaps one day, when everyone isn’t under tremendous pressure to earn money to survive, when we have enough leisure time both to feed our bodies and nourish our souls, when people fully own and control the means of creating and sharing wealth, we can all grow food in our communities and share the surpluses with each other.

For now, it helps to live according the permaculture ethics of Earth Care, People Care, and Fair Share.

Stop buying so much unnecessary stuff. Simplify your lifestyle. Cut back your consumption. Work with others to start a community food garden. Live with a more intentional, slower pace. Take an interest in issues that affect your community. Put some herbs on your windowsill. Read and share with others what you’ve learned. Let go of the urge to get everything right this instant. Cultivate patience. Practice kindness. Consistently. Consciously.

After spending all day digging, planting, and watering trees, Julia and I are flat-out exhausted. But it’s totally worth it. I bet, if the plants could talk, they’d laugh at us and thank us for adding to their already crowded, teeming ecosystem. In a permaculture field, there’s always room for one more plant.

I look around me and see we’re all grinning, taking turns drinking and pouring tea. We ask what we’ll have for dinner and get the usual answer: lentils and pulses.

The sun’s setting and the air begins to cool, but these words keep my heart warm as we make our way back to the tents:

Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.

– Arundhati Roy

P.S. Julia and I were amazed to later learn that her parents met the permaculture guru Bill Mollison in the early 1980s during one of his talks in rural NSW. We had no idea they were even interested in permaculture! It’s beautiful how life comes full circle like that.